The Non-Fatal Offences - Explaining the Law for Law Students

- teachlawhub

- May 11, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Oct 19, 2025

The law of non-fatal offences against the person covers a range of criminal actions where someone is harmed but not killed. These offences play a crucial role in protecting people from violence and threats, and they range from minor incidents like a push to serious injuries like broken bones. This blog will break down the actus reus (the physical element) and mens rea (the mental element) of each non-fatal offence, along with explaining some of the key case law to help you remember the rules, (don't forget there are lots of other cases that can be used too).

Assault (Common Law, charged under Section 39 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988)

Assault occurs when the defendant causes the victim to apprehend immediate and unlawful force. It is important to note that there doesn’t have to be any physical contact or injury, it’s all about what the victim thinks is going to happen. The actus reus of assault can be committed through words, gestures, or even written communication.

In the case of Constanza (1997), the defendant sent over 800 threatening letters to a former colleague, followed her home, and even stole items from her washing line. The victim was in fear and apprehended immediate and unlawful force due to the defendants’ actions. The court confirmed that written words can amount to an assault if they cause the victim to fear immediate force. And, ‘immediate’ doesn’t mean instant, but it does mean imminent.

However, not every threat will count. In the case of Tuberville v Savage (1669), the defendant placed his hand on his sword and said, “If it were not assize-time, I would not take such language from you.” Because he made it clear that he wasn’t going to attack (since judges were in town), there was no assault. This case shows that words can also negate an assault if they make it clear that no harm is actually going to happen.

The mens rea for assault is the intention or recklessness to cause the victim to apprehend immediate unlawful personal violence. The defendant must either want this result or realise there is a risk it will happen and take that risk anyway.

Battery (Common Law, charged under Section 39 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988)

Battery is the application of unlawful force to another person. Unlike assault, battery involves physical contact, but even the slightest touch can be enough provided it is not lawful (for example, a tap on the shoulder to get someone’s attention might be allowed, but a push is not).

In the case of Collins v Wilcock (1984), a policewoman grabbed a woman’s arm without making an arrest. This case confirms that that the force used must be unlawful and can include the slightest touch.

Additionally, in the case of Thomas (1985), a school caretaker touched the hem of a 12-year-old girl’s skirt. The court held that the touching of clothing can be sufficient for a battery. So yes, even touching or grabbing clothing counts.

The mens rea for battery is intention or recklessness as to applying unlawful force. As long as the defendant means to or is aware of the risk of physical contact and takes it, the offence is complete.

Assault Occasioning Actual Bodily Harm (ABH) – Section 47 Offences Against the Person Act 1861

Section 47 ABH involves either an assault or a battery that causes actual bodily harm, this means that there must be some physical or psychological injury, but not really serious. This is a more serious offence than simple assault or battery and can be tried in either the Magistrates' Court or the Crown Court, depending on the seriousness of the case.

In the case of Miller (1954), the court explained that actual bodily harm means any injury that interferes with the health or comfort of the victim, even if it's not permanent or serious. The case involved a man who attacked his wife, causing her to suffer nervous shock.

Later, in the case of Chan Fook (1994) the court clarified that psychiatric injury can also count as ABH, but it must be a medically recognised condition, not just emotions like fear or distress. In this case, the defendant accused the victim of stealing an engagement ring. The victim was locked in a room and jumped out of a window to escape, suffering psychological harm.

The mens rea for ABH is the same as for assault or battery, the intention or recklessness to cause the assault or battery. In the case of Savage and Parmenter (1991), the defendant threw a drink at her husband’s ex-girlfriend and accidentally cut her with the glass. The court confirmed that the defendant didn’t need to intend or foresee the actual harm, just the initial assault or battery.

Grievous Bodily Harm / Wounding – Section 20 Offences Against the Person Act 1861

Section 20 covers more serious injuries, those that are considered “grievous” (meaning really serious) or that amount to a wound (a break in the skin). The offence is triable either way and carries a maximum sentence of five years.

The case of JCC v Eisenhower (1983) made it clear that a wound must involve a break in the skin – internal bleeding alone isn’t enough. In that case, a boy was hit in the eye with a pellet gun, causing internal bleeding but no cut, so it wasn’t classed as a wound.

DPP v Smith (1961) defined grievous bodily harm as “really serious harm.” This includes things like broken bones or serious psychiatric conditions.

In Burstow (1997), the court confirmed that psychiatric injuries can also amount to GBH. The defendant had stalked his ex-partner for months, causing her to develop severe depression. This case proved that psychological harm can be just as serious as physical harm.

The mens rea for s20 GBH is intention or recklessness as to causing some harm – not necessarily serious harm. In Cunningham (1957), the court said that the word “maliciously” means that the defendant either intended or was subjectively reckless about causing some harm.

Grievous Bodily Harm / Wounding with Intent – Section 18 Offences Against the Person Act 1861

Section 18 is the most serious of the non-fatal offences. It involves causing grievous bodily harm or a wound with intent. Unlike section 20, this offence is indictable only, meaning it must be tried in the Crown Court and can carry a sentence of up to life imprisonment.

The actus reus is the same as for section 20, causing really serious harm or a wound. What makes section 18 different is the mens rea, the defendant must have intended to cause serious harm or intended to resist or prevent lawful arrest while being reckless as to causing some harm.

In the case of Belfon (1976), the defendant slashed the victim’s face and chest with a razor. The court held that specific intent to cause serious harm is required for a conviction under section 18, recklessness is not enough.

Want more case breakdowns and revision tips? Keep exploring TeachLaw.net and follow us on TikTok @TeachLaw for bite-sized revision videos.

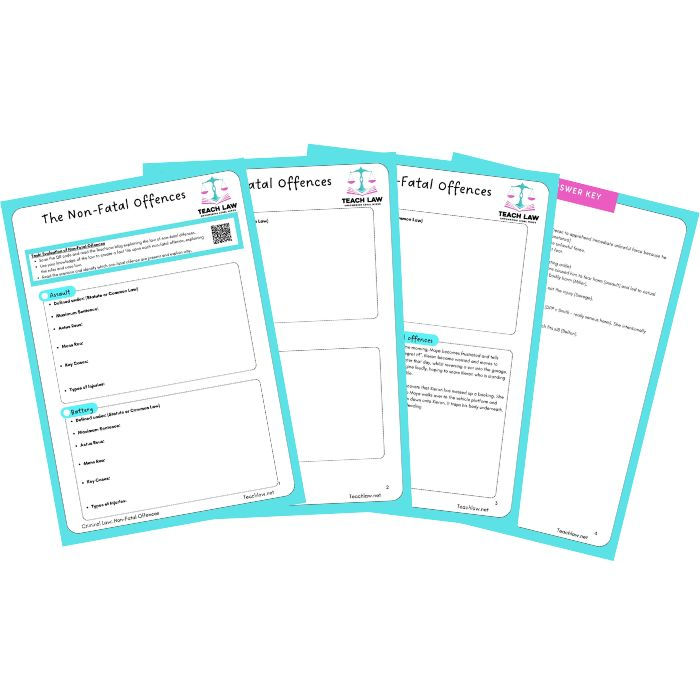

Click to download the free TeachLaw non-fatal offences student activity.

Comments